Reader Warning: Critical discussions of government mistakes and human costs.

In Part 1, I had a more technical discussion of peak complexity with real-life computer failure examples. Part 2 was a brief article with mostly links to make up for my long period of no new articles. It focuses on the value of subtractive solutions over additive solutions. In this article, I am going to focus on the human cost of complexity and the common hierarchical organizational structures we create to deal with complexity. It will be longer and more technical than the previous article. Part 4 to come later will focus on potential solutions to manage complexity. While many people have written on organizational structures, I am going to be more anecdotal here based on my personal observations and experiences because I have not studied other people’s writings too much. To state the obvious, it is going to be incomplete and biased.

I realized that I completely forgot to define what complexity is. I found a Harvard Business Review article titled “Taming Complexity,” and I am simply going to use its definition:

“Complexity” is one of the most frequently used terms in business but also one of the most ambiguous. Even in the sciences it has numerous definitions. For our purposes, we’ll define it as a large number of different elements (such as specific technologies, raw materials, products, people, and organizational units) that have many different connections to one another. Both qualities can be a source of advantage or disadvantage, depending on how they’re managed.

The Federal ID Blunder

Let’s start with an example of how a seemingly boring bureaucratic blunder due to complexity can result in human suffering. In 2022, the federal government announced a significant system update without much fanfare: https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/organization/federal-acquisition-service/integrated-award-environment/iae-systems-information-kit/unique-entity-identifier-update. The goal was to replace the existing proprietary Data Universal Numbering System (DUNS) for assigning unique identifiers to individuals and organizations (businesses, nonprofits, local governments, etc.) with the new Unique Entity Identifier (UEID) system. Individuals and organizations needed these IDs if they were going to get any kind of federal contracts or grants. The DUNS numbers came from a private proprietary system owned by Dun & Bradstreet. I do not know the history of how the federal government came to rely on a private system for something as important as assigning identifiers. It was a weakness they tried to rectify and led to the negative effect as I will explain briefly below.

I was a local government employee who assisted with administering federal grants for low-income individuals and businesses. The government office staff would administer the grants directly or award funds to other organizations, typically nonprofits, for them to administer the grants. When I first learned of the system switch, my thought was, “This might be really bad.” The goal of the new system was to mostly automate background checks of individuals and organizations across all 50 states before assigning the IDs. The obvious barrier to this ideal goal was that states do not have standardized record systems.

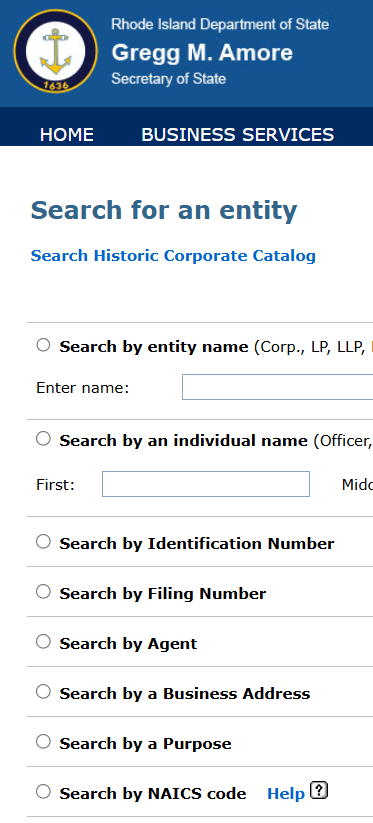

Here is an example comparing Rhode Island and Massachusetts corporation search webpages. The Rhode Island webpage at https://business.sos.ri.gov/CorpWeb/CorpSearch/CorpSearch.aspx shows eight different searchable fields:

The MA corporation search webpage at https://corp.sec.state.ma.us/corpweb/CorpSearch/CorpSearch.aspx, on the other hand, only has four searchable fields:

RI and MA are physically right next to each other. Ironically, RI has a much smaller population, yet its webpage allows for more detailed searches. As of 2023, MA has about 7 million people while RI has 1.1 million. If two contiguous states cannot harmonize their corporation search webpages, what about the remaining 48 states and outlying territories? Would federal government employees and their consultants in charge of this significant project be able to come up with a system that is able to communicate with all the different systems on time and without glitches? Here is the answer: https://federalnewsnetwork.com/reporters-notebook-jason-miller/2022/11/50000-companies-on-hold-because-of-gsas-uei-validation-problems/

Also a person on Reddit wondered: https://www.reddit.com/r/grants/comments/yw9t7h/has_anyone_else_been_having_trouble_with_renewing/?rdt=55947

The failure did not only affect well-off individuals and businesses that have contracts with the federal government. Low-income individuals and businesses who rely on federal grants such as HUD’s Community Development Block Grant were affected. People who already had their DUNS numbers set up had less issues since much of the transitions happened automatically. People who newly applied for assistance and had to get new IDs often ran into the above issue and had no sense of when the issue would be resolved. Looking at the other side of the desk, what if you were one of the public-facing government employees who had to tell people that their applications for assistance were going to be delayed due to a nationwide system issue?

I do not think the people who implemented the change were malicious. It makes sense to get away from a proprietary system owned by a private corporation to a more standardized system owned by the government. This is the federal website on UEID, which does not offer much details about the motivation and history: https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/organization/federal-acquisition-service/fas-initiatives/integrated-award-environment/iae-systems-information-kit/unique-entity-id-is-here

The dilemma of any society with complex private (businesses, nonprofits, etc.) and public (government agencies at various levels) organizations is that as complexity increases due to having many parts (people, departments, processes, regulations, data, etc.), the difficulty of managing the organizations and the risk of massive problems increase as well. No matter how many clever techniques people employ, a high level of complexity and subsequent risk is unavoidable. If an organization realizes that its current processes have significant weaknesses and need a major reform, there is no guarantee whatsoever that the reform will be painless or effective. Let’s look at some simplified examples of organizational structures to explore how complexity can lead to painful effects.

Organizational Complexity is Hard to Avoid

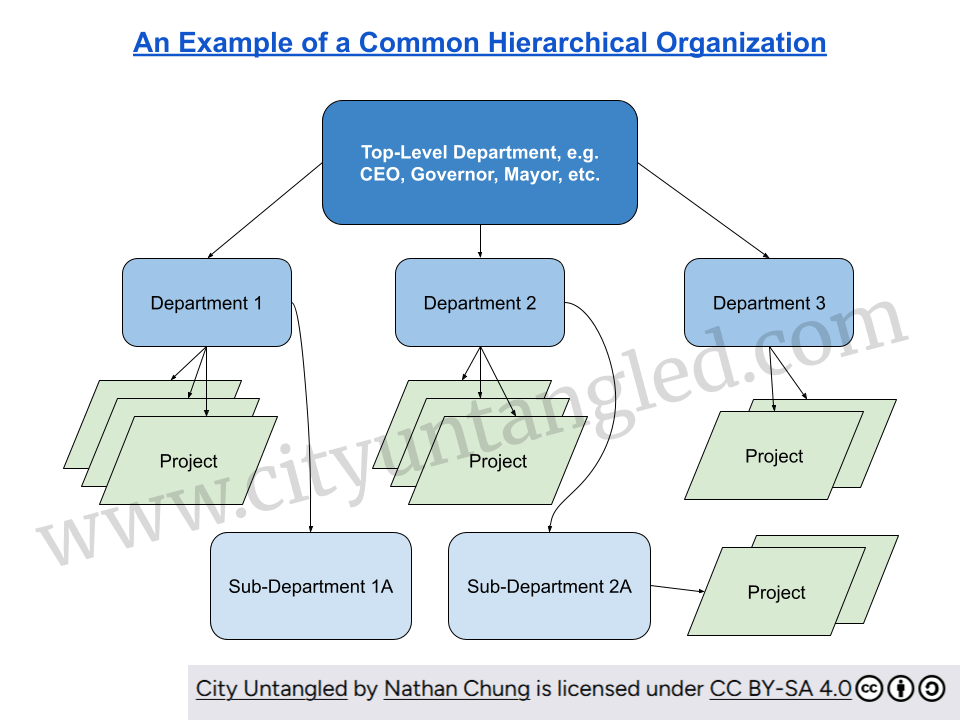

Hierarchy and compartmentalization are some of the most common organizational techniques for managing complexity from what I have seen. Most organizations of sufficient complexity I observed have at least three levels of hierarchy that distributes powers and responsibilities across different levels and departments. Here is an abstract diagram of such an organization.

The topmost departments are usually the ones with the most oversight and power over the lower ones. By power, I mean the ability to give orders, move around, and fire people in the lower levels. The tradeoff is that due to overseeing many departments and individuals, the people at the topmost level tend to not have specialized skills and awareness of details like the people in the the lower departments. They might have had them at one point when they started at the lower levels but lost them as they climbed up the hierarchy.

If you have worked for or interacted with these types of organizations, you probably experienced at least one of these challenges:

- You are outside the organization, e.g. a customer, and have an issue you need help on from the organization. You have no idea which department to contact. In the worst case, you call the organization and get a robot on the other side of the phone that keeps you in an infinite loop.

- You are working within an organization and a new project or issue arises. The departments have no clear idea whose jurisdiction it is. This phenomenon is related to “silo mentality.” If it is government-related, you might even go beyond departmental confusion and get into a dispute over which government agency has jurisdiction, i.e. turf war. A hilarious fictional example is from the 2017 drug heist movie, American Made where the drug mule played by Tom Cruise gets arrested by multiple agencies. Profanity warning: https://youtu.be/dNwER7xIXR8?feature=shared

- As jobs become more specialized, it becomes harder to fill vacancies for specialized roles either through hiring new people or training people within the organization.

- As the hierarchy gets deeper, the departments at the higher level are less aware of the detailed issues going on at the ground-level. Conversely, departments at the lower level who specialize in resolving specific sets of issues are not aware of the broader combination of issues occurring throughout the organization or how the departments fit together. Again, the “silo mentality.”

The challenge faced by any society of sufficient complexity is: To achieve complex goals, you need complex organizations, regulations, processes, and specialists. The hierarchical organization described above is almost a necessity to achieve complex goals. For those who say we can do away with all these complexities by avoiding complex goals, I will throw out a few examples of the goals that many people in industrialized nations like: plumbing with flush toilets, smartphones, computers, Internet, cars, large concerts, and sports stadiums. You can do away with a lot of complexity if you are willing to give these up.

Other Types of Organizations

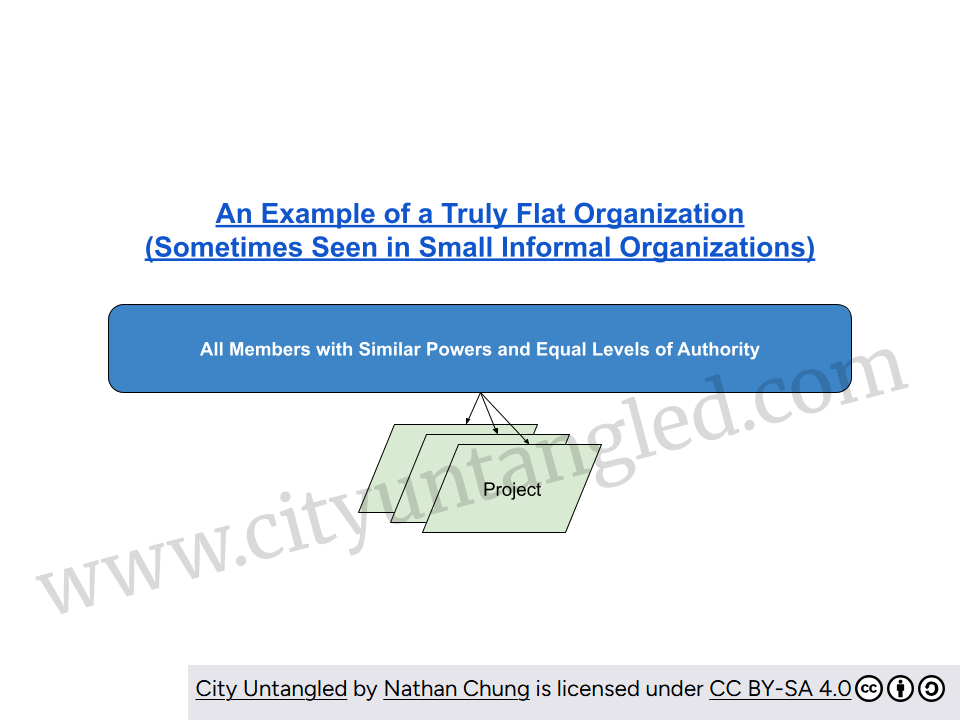

Organizations with structures different from the common hierarchical structure I shared above exist. They tend to be small businesses with a narrow set of goals. One structure I have very rarely seen is the truly flat organization where all members have very similar levels of powers. Think of a small hiking group composed of people from similar age groups with similar abilities. Even in such an organization, one person often assumes the leadership role, but the hierarchy is still minimal compared to other organization types. Now, if the hiking group meets regularly and the leadership roles rotate, it would be truly flat.

Another type of organization, which I nicknamed “pseudo-flat organization,” exists. These are often small businesses with just two levels of hierarchy – the owners (or managers) and the employees. I had incidents where the owners or managers tried to present the organizations as equitable and flat environments. I found that they can sometimes be one of the worst places to work for due to the amount of power the higher-ups have with no middle manager oversight or power diffusion. A specific type to avoid in many cases is “the family business” where the owners give managerial role to their adult children with minimal work experience so they can “learn the family business.” You can argue that it has three levels of hierarchy since the adult children are in the middle as managers. In some cases, they basically function as owners with their parents submitting to their demands, resulting in a two-level hierarchy.

What are Some Solutions?

The next article, Part 4, will cover some possible solutions. It would probably be the last article in this series, at least for a while. I am leaving with this list of thoughts.

- We live in a finite world with physical and biological limits. Each living or non-living being has a unique set of limits. People who are advocating for solutions that add more complexity would need to recognize these limits and realize that what is a manageable level of complexity for one being is not manageable for another.

- Related to above, infinitely increasing complexity is not sustainable.

- Policies on how you organize and label data matters A LOT.

- In general, you want to explore subtractive solutions first before exploring additive solutions since they tend to cost less resources and do not have as many side effects.